Why Having a To-Do List Isn't Enough

An Academic Perspective on Cognitive Neuroscience and Productivity.

Introduction

In the fast-paced world of executive leadership, productivity is paramount. To-do lists have long been touted as a cornerstone of effective time management and organizational skills. However, as an academic neuroscientist, I argue that merely having a to-do list is insufficient for achieving optimal productivity. Understanding the cognitive processes involved in task management and execution can provide deeper insights into why a to-do list alone might fall short and how executives can harness neuroscience to enhance their efficiency.

The Cognitive Neuroscience of Task Management

The human brain is a complex organ with distinct regions responsible for different cognitive functions. The prefrontal cortex (PFC), located at the front of the brain, plays a crucial role in executive functions, including planning, decision-making, and impulse control (Miller & Cohen, 2001). When creating a to-do list, we engage the PFC to organize and prioritize tasks. However, merely listing tasks does not guarantee that they will be completed efficiently or effectively.

The Limitations of To-Do Lists

1. Cognitive Overload

A long and detailed to-do list can overwhelm the PFC, leading to cognitive overload. This state hampers our ability to prioritize and focus on individual tasks, resulting in reduced productivity and increased stress. Neuroscientific research suggests that breaking down tasks into smaller, manageable chunks can alleviate cognitive overload and enhance focus (Goldberg, 2001).

2. Procrastination and Decision Fatigue

To-do lists often lack temporal context, making it easy to procrastinate. Without clear deadlines or time allocations, the brain tends to delay tasks perceived as difficult or unpleasant. Additionally, decision fatigue can set in when continuously deciding which task to tackle next (Baumeister et al., 1998). Structuring tasks with specific timeframes and employing techniques such as time-blocking can mitigate these issues.

3. Lack of Emotional Engagement

To-do lists are typically pragmatic and devoid of emotional context. Neuroscientific studies indicate that emotions play a significant role in motivation and goal-directed behavior (Damasio, 1994). Integrating emotional elements into task planning, such as visualizing the positive outcomes of completing a task or setting emotionally meaningful goals, can boost motivation and drive.

The Power of Checklists in Boosting Productivity

While to-do lists alone may have limitations, checklists—when used effectively—can significantly enhance productivity. Recent research has highlighted the benefits of checklists in increasing motivation and productivity through the release of dopamine.

Dopamine and Action

Dopamine, once thought to be solely the "pleasure hormone," is now understood to be an "action hormone." Every time an action is completed, such as checking off an item on a checklist, the brain releases a small surge of dopamine. This release creates a feeling of satisfaction and accomplishment, motivating further action (Schultz, 1998). The cumulative effect of these small surges can lead to sustained productivity.

Enhancing Checklists with Neuroscience

1. Recording Small Accomplishments

To maximize the dopamine effect, it is beneficial to list and record even small accomplishments throughout the day. If a task is completed that wasn't initially on the list, adding it and checking it off can still trigger a dopamine release, reinforcing the habit of productivity.

2. Scheduling Tasks

Integrating the checklist into a structured schedule can further enhance productivity. By organizing tasks in a logical order and assigning specific time slots, individuals are more likely to stay on task and avoid distractions. This approach not only increases dopamine circulation but also helps in prioritizing tasks and managing time more effectively (König et al., 2005).

3. Physical Interaction

Physically writing down tasks and checking them off, as opposed to merely deleting them on a computer, can amplify the dopamine effect. The physical action of marking a task as complete provides a more substantial sense of achievement (Gershon & Eickhoff, 2013).

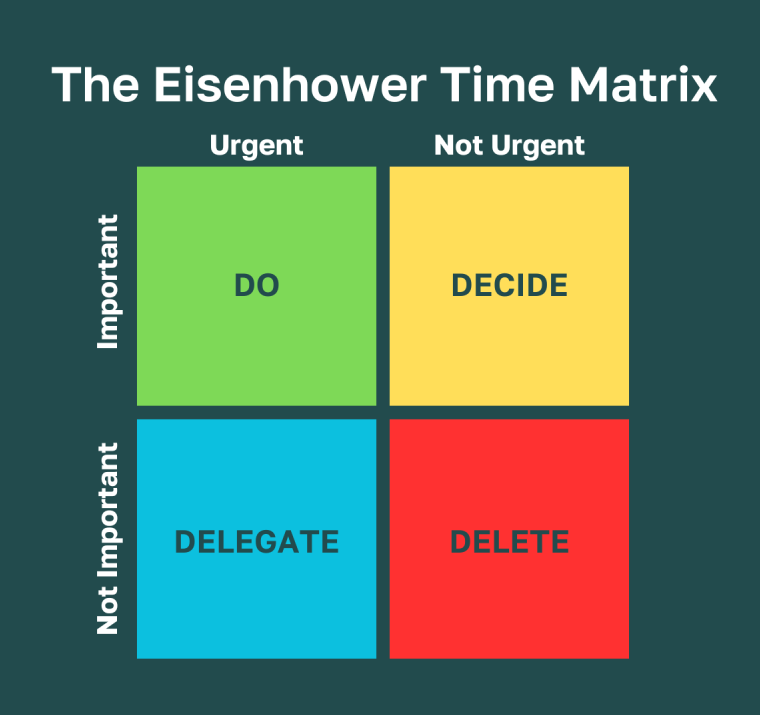

Enhancing Productivity Through Neuroscience-Based Strategies

1. Prioritization and Goal Setting

Incorporating neuroscience-based techniques such as the Eisenhower Matrix can help prioritize tasks based on urgency and importance. Setting clear, achievable goals activates the brain’s reward system, releasing dopamine and fostering a sense of accomplishment, which in turn motivates further action (Locke & Latham, 2002).

2. Mindfulness and Focus

Practicing mindfulness can improve cognitive control and reduce distractions. Neuroscientific research shows that mindfulness meditation strengthens the PFC and enhances its connectivity with other brain regions, improving attention and focus (Zeidan et al., 2010). Incorporating short mindfulness sessions into the daily routine can significantly enhance productivity.

3. Chunking and Habit Formation

Breaking tasks into smaller chunks and creating routines can transform daunting tasks into manageable ones. Habit formation leverages the brain’s basal ganglia, making certain behaviors automatic and reducing the cognitive load on the PFC (Graybiel, 2008). Establishing consistent work routines and automating repetitive tasks can free up cognitive resources for more complex decision-making.

Conclusion

While to-do lists are a valuable tool for organizing tasks, they are not a panacea for productivity challenges. Understanding the cognitive neuroscience behind task management reveals the limitations of relying solely on to-do lists. By integrating neuroscience-based strategies and effectively using checklists, executives can enhance their productivity, reduce cognitive overload, and achieve their goals more efficiently. Embracing these insights can lead to a more balanced and effective approach to task management, ultimately driving success in the demanding world of executive leadership.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252.

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Putnam Publishing.

Gershon, A., & Eickhoff, M. (2013). The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. Annals of Internal Medicine, 158(6), 484-485.

Goldberg, E. (2001). The Executive Brain: Frontal Lobes and the Civilized Mind. Oxford University Press.

Graybiel, A. M. (2008). Habits, rituals, and the evaluative brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 31, 359-387.

König, C. J., Kleinmann, M., & Höhmann, W. (2005). Time allocation in job interviews: An analysis of interviewers' decisions. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 13(4), 344-353.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705.

Miller, E. K., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24(1), 167-202.

Schultz, W. (1998). Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology, 80(1), 1-27.

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597-605.